Surgical Essentials: Scalpel Blades and Handles

/It’s been a while since we did a surgically-focused episode - we’ve previously done a series on laparoscopy and hysteroscopy, as well as on sutures and needles. Today, let’s focus in on an essential surgical instrument - the scalpel!

Additional reading: British Journal of Surgery Oct. 2022 review (also, the author Dr. Ron Barbosa is on Twitter and does some great surgical tweetorials!)

History of the modern scalpel

Morgan Parker, a 22 year old engineer at the time, patented a locking scalpel handle and blade system in 1915 to replace what previously were often single-piece instruments without a replaceable blade.

His original design (slightly modified) is still what we use today!

Parker initially numbered handles 1-9 and blades 10-20; while this has been somewhat modified/expanded, the nomenclature largely remains the same.

We’ll talk about the most common handles and blade types today.

Scalpel handles

You’ve probably never had to ask for these in a surgical tray – so let’s review!

The number three handle is most commonly used in surgical specialties:

Flat shape

Some serrations near the blade attachment area to provide better grip for surgeon

Fits blade numbers 10-19

Modifications include the 3L (long-handle scalpel) and 3L angled (long-handle with a slight angulation).

The number four handle fits larger blades (#20 and above), but otherwise is very similar to the #3.

The number seven handle is very narrow and meant for precise, fine work – not typically used in OB/GYN or subsepcialties – more common in head/neck/ENT, plastics, neurosurgery, and dentistry.

Barbosa, BJS, 10/2022

Scalpel blades

You may be more familiar with these, but likewise may not have had to ask for them before!

The number ten blade is used to make longer skin incisions for laparotomy, or for shorter cuts where a wide blade is ideal (i.e., hysterotomy).

This is probably what you’re most familiar with in OB/GYN applications.

You may also encounter a number 22 blade, which is essentially a larger version of the #10.

The number eleven blade is triangular, long, and has a sharp point with an edge on one side.

Its shape is best suited for a stab incision - for instance, for laparoscopic port incisions, Bartholin’s gland cruciate incisions, and the like.

Its shape is not great though for excising anything - it’s really pointy!

The number fifteen has a small, curved cutting surface as well as a pointed tip.

You can use this for a stab incision at the point, and a more controlled incision for excising tissue with the curved portion.

Great for working in tight spaces versus a 10 blade for excision (i.e., oncology cases or urogyn cases – think about sharply cutting on your cardinal ligament bites – a 15 blade on a 3L handle is great for this!)

Also great for stab incisions, and many folks may prefer a 15 to an 11 blade for Bartholin’s or laparoscopy incisions.

10 blade (top), 11 blade (middle), 15 blade (bottom)

Scalpel blade materials, and disposables versus regular blade/handles

Disposables are great and often very available for outpatient procedures or for emergencies

The blades between disposable and regular blades are the same shape/size/nomenclature, so there’s no difference in that regard.

However, the regular blades tend to be a bit thicker on the back, non-cutting surface of the blade, which gives a bit more structure and may feel sturdier when cutting.

In terms of materials, the vast majority of scalpels we use will be made of carbon steel or stainless steel.

Steel blades can also have other compositions or coatings that can help with retaining sharpness and/or resisting rusting/corrosion.

Other materials used in modern blades include ceramic, titanium, diamond, sapphire, and obsidian.

Many of these - especially ceramic and obsidian - are extremely sharp, and can be chosen because they are non-magnetic – so for MRI-guided procedures, they are preferred. However, they are so sharp that they can be very dangerous in poorly trained hands - so we wouldn’t use these unless you have a great reason to do so!

How do I hold a scalpel?

Intern struggle – and the truth is that it depends!!!

For larger blades - i.e., a #10 blade or a #20 or above - the best grip is a “palmar” or “violin grip,” in which you have your index finger atop the handle, and use your other fingers to hold the body of the handle, with the back part of the handle under your palm.

This allows for precision with the long, wide cuts you would typically make with this blade.

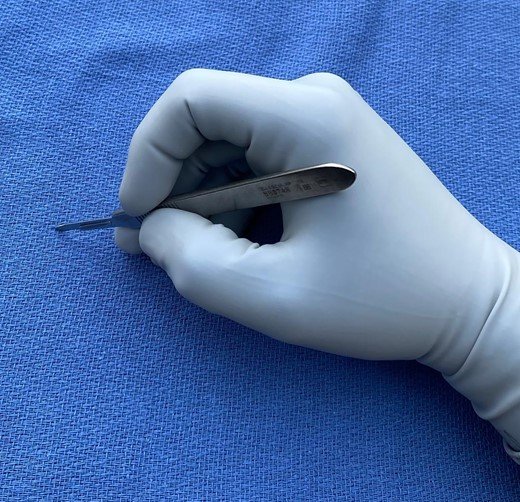

For smaller, pointier blades – a #11 or #15 - the “pencil grip” is preferred.

This allows for precision with your “stab” incision or for those tight/deeper spaces.

Barbosa, BJS 10/22: Palmar/”Violin” grip, for larger blades (#10, #20 and above)

Barbosa, BJS 10/22: Pencil grip, for smaller blades (#11, #15)